by Rachel French

As educators, we know that we cannot possibly teach children everything they need to know and be able to do in the future. We also know that many of our students will work in jobs that do not yet exist.

So how do we prepare our students for this rapidly changing world?

We help them take a deep dive, moving from ‘knowing’ to ‘understanding.’ We must also make sure that we are actively promoting opportunities for them to transfer learning.

It is one thing for a student to be able to recite a mathematical formula and solve problems when they know it will be assessed, but it is entirely another for them to be able to recognize the opportunity to use the formula in their scientific investigation.

Will the student who has studied Christopher Columbus have a deeper understanding of the motives of film director James Cameron and his deep-sea exploration, or of Elon Musk and his ambitious space-missions?

The ability to transfer and apply learning to new contexts is often assumed, however, research shows students typically perform poorly when learning transfer is required (Bransford, 2000). The time has come for us as educators to become more intentional about supporting students in the transferring of learning.

In a traditional classroom, the focus is on factual recall and summarizing findings. Repeated practice is considered the basis for the development of skills and strategies.

In a Concept-Based Inquiry classroom (Erickson et.al, 2017 and Marschall and French, 2018) we teach for understanding and actively seek opportunities for students to transfer their learning.

We help students develop a range of strategies to organize their findings and make connections to articulate generalizations.

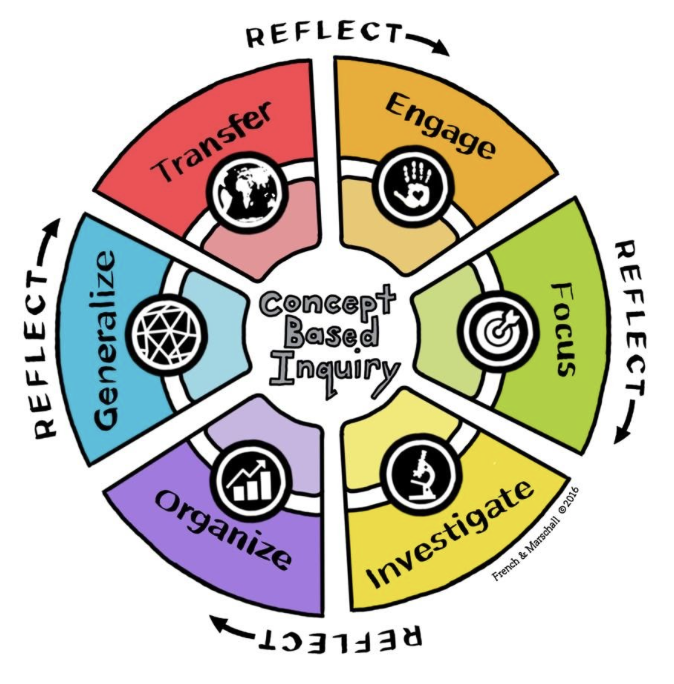

Our inquiry approach (French and Marschall, 2016) promotes a deeper understanding of conceptual relationships.

Research shows with a focus on understanding rather than emphasizing the recall, repetition and summarization, students are better able to transfer their learning (Bransford, 2000).

As educators, we can no longer afford to assume that our students transfer their understandings. We must actively promote and create opportunities for four different types of transfer:

1: Understanding New Events and Situations

We actively support students in transferring learning to new events and situations. Having completed a Unit ‘Ellis Island – The History of Immigration to the United States | 1892-1954’ students have come to understand that, “Conflict and political change can motivate people to migrate in search of security, new opportunities and freedom.” When reading news reports of Syrian refugees seeking asylum, we invite students to make connections to their own ancestors who migrated to the United States escaping persecution. This also helps them to understand why there is an influx of refugees in their local community.

We actively support students in transferring learning to new events and situations. Having completed a Unit ‘Ellis Island – The History of Immigration to the United States | 1892-1954’ students have come to understand that, “Conflict and political change can motivate people to migrate in search of security, new opportunities and freedom.” When reading news reports of Syrian refugees seeking asylum, we invite students to make connections to their own ancestors who migrated to the United States escaping persecution. This also helps them to understand why there is an influx of refugees in their local community.

2: Testing and Justifying Generalizations

As students learn they naturally build their own ideas and theories about the world. At times, students will overgeneralize. Having studied Martin Luther King and Mahatma Gandhi, students generalize that “Leaders act to improve the civil rights of others.” Encouraging students to transfer this idea, considering the leadership of Hitler or Pol Pot, helps them to refine their thinking and reconsider the relationship between motivation, leadership and civil rights.

3: Applying Learning and Taking Action

In a Concept-Based Inquiry classroom, we can also transfer learning by taking action. In their science class, students have come to understand that Social isolation can lead to depression, difficultly sleeping, and other health complications. As a result, a small group of students decide to set up a group to regularly visit the local nursing home and play board games with the residents.

In a Concept-Based Inquiry classroom, we can also transfer learning by taking action. In their science class, students have come to understand that Social isolation can lead to depression, difficultly sleeping, and other health complications. As a result, a small group of students decide to set up a group to regularly visit the local nursing home and play board games with the residents.

4: Making Predictions and Hypothesizing

Finally, we promote the transfer of learning as students hypothesize and make predictions. We help students to resist the urge to guess by taking the time to think about what they already understand. This helps them to make informed and reasoned predictions. For example, the student who is investigating genetic inheritance is encouraged to return to their understanding of probability and chance.

Finally, we promote the transfer of learning as students hypothesize and make predictions. We help students to resist the urge to guess by taking the time to think about what they already understand. This helps them to make informed and reasoned predictions. For example, the student who is investigating genetic inheritance is encouraged to return to their understanding of probability and chance.

Want to know more?

In our book, ‘Concept-Based Inquiry in Action,’ Carla Marshall and I have developed a range of tools and strategies that scaffold students thinking and promote the transfer of understanding.

You can get a copy of the book by clicking here, or alternatively you can like our Facebook page to keep up to date on our upcoming online and face to face workshops.

Rachel French

Concept-Based Consultant and Coach

Bestselling Author

Director of Professional Learning International and Co-founder of Connect the Dots International

Twitter: https://twitter.com/ProLearnInt

Facebook Group: https://www.facebook.com/groups/conceptbasedinquiry

Linked In: https://www.linkedin.com/in/rachel-french-pli/

References

Bransford, J. (2000). How people learn. Washington, DC: National Acad. Press

Erickson, H., Lanning, L., & French, R. (2017) Concept-based curriculum and instruction for the thinking classroom. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Marschall, C., & French, R. (2018) Concept-Based Inquiry in Action.